There is a famous study in nonprofit marketing that shows that an appeal that tells the story of a child does better than an appeal that tells that same story with information about the general problem of poverty in Africa. Even more oddly, a story of one boy did as well as the story of one girl; both did better than the story of the boy and the girl. The study is here and it is both fascinating and disheartening.

We humans think in simple narrative. We are used to hearing a story of a person (then using availability bias, which we talked about, to generalize). When we hear the story of a person, we react to it with emotion and affect. When we hear the story of many people, we react to it with logic and calculation. Or as Stalin put it: “If only one man dies of hunger, that is a tragedy. If millions die, that’s only statistics.”*

Image credit here. Odd that Stalin and Mother Teresa had similar sentiments on this. And I don’t think anyone has ever seen them in the same room at the same time…**

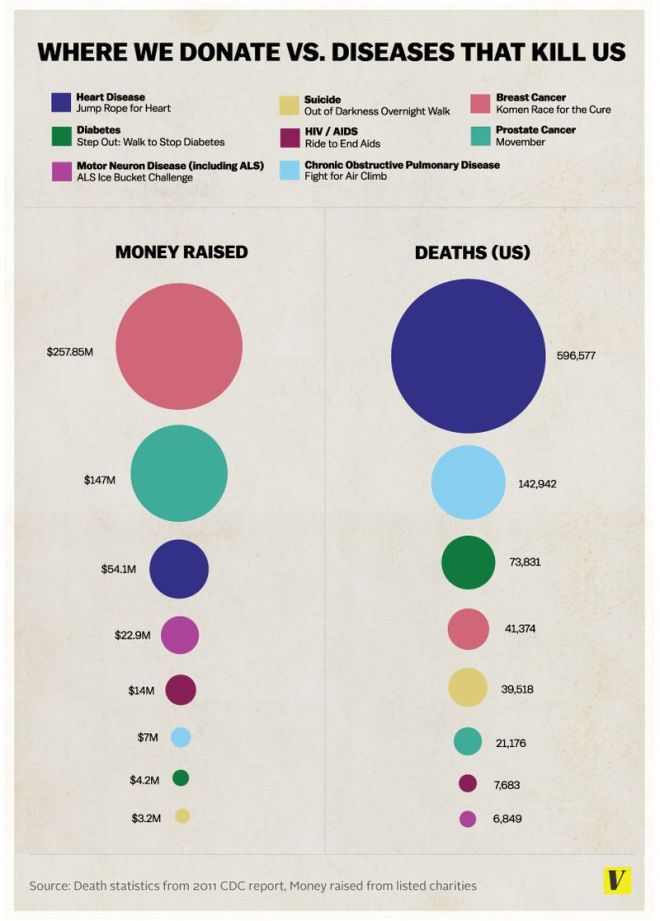

Unfortunately, this leads to us (in theory) misallocating our resources. Vox did an illustration of the types of cancer people donate to, versus what they die of.

This seems to focus on special events and looks at one organization per disease, so it isn’t perfect but is emblematic of this problem. In 2010, the humanitarian aid response to the Haiti earthquake (which affected 3 million people) was more than 3 billion dollars. The flood in Pakistan (which affected an estimated 20 million people) received only 2.2 billion dollars. (study here) People donate relatively the same amount to save 2,000, 20,000, and 200,000 birds.

So the rule you could get from this is to tell only one story at a time. Which is not a bad rule.

However, your organization likely has a scope you want to achieve. You don’t just want to help one person. You want to help one person, then another, then another, etc., until your problem is solved and you can take up golf or something.

So how do you talk about scope without turning off your donors?

One way is to talk about scope and statistics, but to do it with the right donors. I would point you to the post I did about a month ago about the study that shows that statistics depress response among smaller donors, but increase it among larger donors. Thus, you can save it for the right audience.

Another solution that was interesting to me came from a study in the Journal of Consumer Research.

At first, they just found what we’ve been talking about: single identified victim works better than large numbers of victims. Scope blindness in action.

However, you can get people to donate more to large numbers of victims if the victims are seen to be entitative.

This was the point in reading the study that I had to pull out the dictionary. I thought that entitative meant “similar to a walking talking tree from Lord of the Rings.”***

In reality, “entitative” means how much people consider something to be a coherent whole. This can be helped by group membership. In the study, they found that donations to help children were greater when the children were part of the same family, instead of random so-and-sos.

Similarly, they asked about saving butterflies, showing butterflies either flying randomly (low entitativity) or together (high entitativity). The butterfly flock (is that a thing?) raised 69% more on average.

They also found when that in-group had positive qualities, people were more likely to donate. Specifically, when the starving children in Africa were said to be in the same prison, rather than the same family, the group dynamic hurt donations rather than helping them.

So if you are going to talk about multiple people, try to frame them as part of the same in-group and make that in-group as positive as possible. Then, and seemingly only then, will you be able to tell more than one story and get more donations instead of fewer.

* I’d heard a different pithier version of this also (one where if you kill one person, you are a murderer; if you kill a million, you are a conqueror). However, this one seems to have the greatest basis in fact according to Quote Investigator.

** This is a joke, of course. This seems obvious, but one can not be too careful on the Internet. Clearly, Stalin is the evil twin of Mother Teresa.

*** Yes, I know that the ents aren’t really trees. They are treelike guardians that take on the shape of the trees they herd. But I’m trying to get everyone to read to the end of this, not just people who are as nerdy as I am.