Last week, Charity Navigator released its new 2.1 rating system after reassessing its financial ratings. This was an approximation of my reaction:

I’d heard about Charity Navigator 3.0 and thought that maybe they would finally start focusing on nonprofit results. But then they tried to use their lack of expertise to judge the logic models of experts in the field. I argued then as now that I would trust the American Heart Association on how to prevent heart disease more than Charity Navigator, just as I would trust the doctor or nurse in the ER more than an intern at the hospital’s accounting firm.

I was hopeful with this effort was euthanized. And I’d hoped that new leadership and time would change things. But then their new leadership said that (in essence) mail may not make sense for nonprofits (story here). As if we need less money to go to noble causes, not more.

Then they surveyed nonprofit leaders about the effectiveness of their metrics. I gladly participated, telling them what were their most and least helpful metrics (answer: they were all tied for least helpful, in that they are not just not helpful but counterproductive). Again I hoped for change.

What we saw on the first were a couple of tweaks: the manicure to a patient with a sucking chest wound.

This is frustrating, but I believe in the idea of giving insight into nonprofits for those who want it. Like companies, people, or governments, there are good nonprofits and great nonprofits and scam nonprofits and blah nonprofits.

And I like that nonprofits are stepping up to do this. When governments have to get involved, we too often see a cleaver used instead of a scalpel.

Charity Navigator’s own accountability and transparency metrics are very strong and helpful (other than the misguided view of what a privacy policy is). When you don’t have things like an independent board, systems to review CEO compensation, regular audits, and so on, there’s a good chance you might be a scam (or very young as an organization).

But Charity Navigator continues to prop up the overhead myth, as described here. While this is the most grievous sin, it is by no means the only one. Thus, this week, we’ll take a look at why you should not only ignore the Charity Navigator financial metrics, but actively do the opposite.

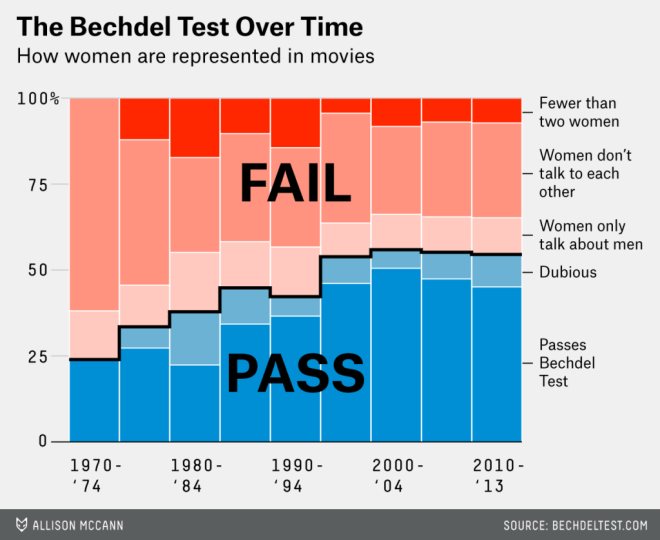

With the new Charity Navigator ratings, program expenses are on a rating scale instead of using the raw value. This focuses even more on the fallacious overhead rate, giving greater emphasis to differences among nonprofits. In my post on the overhead myth, I talked about how a focus on overhead generally will prevent a non-profit from making the investments needed to grow. Now, let’s look at a specific case of how focusing on fundraising expenses hurts growth, that of diminishing marginal returns.

Perhaps like me your econ class was at 8 AM, so let me explain with a thought experiment. Let’s say you were going to do a mailing to only one person. You’d clearly pick out the best possible donor to send to — the person who gives you a significant donation every single time.

Now, let’s say you found an extra couple of quarters in your couch and wanted to mail a second person. You’d find another person who is almost as good as the first — maybe they give a significant donation 99% of the time.

Let’s repeat this 10,000 times. Now you are getting into people who are either less likely to donate or who will likely give smaller gifts. Your revenues per mailing sent will still be very good — it will more than pay for itself by a wide margin — but not as good as that first person.

Now repeat 100,000 times. The potential donors are getting even more marginal here. But your expenses have barely gone down.

This is diminishing marginal returns in action. As you try to reach more people and grow, your outreach becomes more probabilistic and less profitable.

But it’s still profitable. (In the real world, you would hopefully be looking at this along the donor axis rather than the piece axis, asking if each piece added to lifetime value, but let’s not gum up the thought experiment).

If you had a magic box into which you could put $1, and get $1.10 in lifetime value out, should you do it? Many of we fundraisers would be putting money into that box like a rat designed to get a, um, pleasurable experience when it pushed a level. And we’d be right to. More money = more mission.

But by focusing on the cost of fundraising, CN would have you cut off at the 10,000 mark (or not to mail at all). Less money, fewer donors, less mission.

That’s the starvation cycle in action on the fundraising side of things. And it’s made even worse by Charity Navigator’s stubborn refusal to allow for joint cost allocation of joint fundraising/programmatic activities, which we’ll cover tomorrow.

can do that most American of things — blame the French — for this one. M technically stands for mille, which is French for one thousand. You may have encountered this in the dessert mille-feuille, which is French for a cake of a thousand sheets, or in the card game Mille Bourne, which is based on being chased by a thousand angry Matt Damons.)

can do that most American of things — blame the French — for this one. M technically stands for mille, which is French for one thousand. You may have encountered this in the dessert mille-feuille, which is French for a cake of a thousand sheets, or in the card game Mille Bourne, which is based on being chased by a thousand angry Matt Damons.)