Yesterday, I said you can get a good idea of who your donor is through their actions. The trick here is that you will never find donor motivations for which you aren’t already testing. This is for the same reason that you can’t determine where to build a bridge by sitting at the river and looking for where the cars drive in trying to float across it, Oregon-Trail-style.

Damn it, Oregon Trail. The Native American guide told me to try to float it.

Don’t suppose that was his minor revenge for all that land taking and genocide?

To locate a bridge, you have to ask people to imagine where they would drive across a bridge, if there were a bridge. This gives you good news and bad news: good news, you can get information you can’t get from observation; bad news, you get what people think they would do, rather than what they actually will do.

True story: I once asked people what they would do if they received this particular messaging in an unsolicited mail piece. Forty-two percent said they would donate. My conclusion — about 40% of the American public are liars — may have been a bit harsh. What I didn’t know then but know now is that people are often spectacularly bad at predicting their own behavior, myself included. (“I will only eat one piece of Halloween candy, even though I have a big bucket of it just sitting here.”)

There is, of course, a term for this (hedonic forecasting) and named biases in it (e.g., impact bias, empathy gap, Lombardi sweep, etc.). But it’s important to highlight here that listening to what people think they think alone is perilous. If you do it, you can launch the nonprofit equivalent of the next New Coke.

“The mind knows not what the tongue wants. […] If I asked all of you, for example, in this room, what you want in a coffee, you know what you’d say? Every one of you would say ‘I want a dark, rich, hearty roast.’ It’s what people always say when you ask them what they want in a coffee. What do you like? Dark, rich, hearty roast! What percentage of you actually like a dark, rich, hearty roast? According to Howard, somewhere between 25 and 27 percent of you. Most of you like milky, weak coffee. But you will never, ever say to someone who asks you what you want – that ‘I want a milky, weak coffee.’” — Malcolm Gladwell

With those cautions in mind, let’s look at what survey and survey instruments are good for and not good for.

First, as mentioned, surveys are good for finding what people think they think. They are not good for finding what people will do. If you doubt this, check out Which Test Won, which shows two versions of a Web page. Try to pick out which version of a Web page performed better. I venture to say that anyone getting over 2/3rds of these right has been unplugged and now can see the code of the Matrix. There is an easier and better way to find out what people will do, which is to test; surveys can give you the why.

Surveys are good for determining preferences. They are not good for explaining those preferences. There’s a classic study on this using strawberry jam. When people were asked what their preferences were for jam, their rankings paralleled Consumer Reports’ rankings fairly closely. When people were asked why they liked various jams and jellies, their preferences diverged from these expert opinions significantly. The authors write:

“No evidence was found for the possibility that analyzing reasons moderated subjects’ judgments. Instead it changed people’s minds about how they felt, presumably because certain aspects of the jams that were not central to their initial evaluations were weighted more heavily (e.g., their chunkiness or tartness).”

This is not to say that you shouldn’t ask the question of why; it does mean you need to ask the question of why later and in a systematic way to avoid biasing your sample.

Surveys are good for both individual preferences and group preferences. If you have individual survey data on preferences, you absolutely should append these data to your file and make sure you are customizing your reasons to give to the individual’s reason why s/he gives. They also can tease out segments of donors you may not have known existed (and where you should build your next bridge.

Surveys are good for assessing experiences with your organization and bad for determining complex reasons for things. If you have 18 minutes, I’d strongly recommend this video about how Operation Smile was able to increase retention by finding out what donors’ experiences were with them and which ones were important. Well worth a watch.

If you do want it, you’ll see that they look at granular experiences rather than broad questions. These are things like “Why did you lapse” or “are we mailing too much?” These broad questions are too cognitively challenging and encompassing too many things. For example, you rarely hear from a donor to send fewer personalized handwritten notes, because those are opened and sometimes treasured. What the answer to a frequency question almost always leads to is an answer to the quality, rather than quantity, of solicitation.

Surveys are good when they are well crafted and bad when they are poorly crafted. I know this sounds obvious, but there are crimes against surveys committed every day. I recently took a survey of employee engagement that was trying to assess whether our voice was heard in an organization. The question was phrased something like “How likely do you think it is that your survey will lead to change?”

This is what I’d call a hidden two-tail question. A person could answer no because they are completely checked out at work and fatalistic about management. Or a person could answer no, because they were delighted to be working there, loved their job, and wanted nothing to change.

Survey design is a science, not an art. If you have not been trained in it, either get someone who is trained in it to help you, or learn how to do it yourself. If you are interested in the latter, Coursera has a free online course on questionnaire design here that helped me review my own training (it is more focused on social survey design, but the concepts work similarly).

You’ll notice I haven’t mentioned focus groups. Focus groups are good for… well, I’m not actually sure what focus groups are good for. They layer all of the individual biases of group members together, stir them with group dynamic biases like groupthink, unwillingness to express opinions contrary to the group, and the desire to be liked, season them with observer biases and the inherent human nature to guide discussions toward preconceived notions, then serve.

Notice there was no cooking in the instructions. This is because I’ve yet to see a focus group that is more than half-baked. (rim shot)

My advice if you are considering a focus group: take half of the money you were going to spend on the focus group, set it on fire, inhale the smoke, and write down the “insights” you had while inhaling the money smoke. You will have the same level of validity in your results for half the costs.

Also, perhaps more helpful, take the time that you would have spent talking to people in a group and talk to them individually. You won’t get any interference from outside people on their opinions, introverts will open up a bit more in a more comfortable setting and (who knows) they may even like you better at the end of it. Or if you hire me as a consultant, I do these great things with entrails and the bumps on donors’ heads.

So which do you want to use: surveys or behavior? Both. Surveys can sometimes come up with ideas that work in theory, but not in practice, as people have ideas of what they might do that aren’t true. Behavior can show you how things work in practice, but it can be difficult to divine deep insights that generalize to other packages and communications and strategies. They are the warp and weft of donor insights.

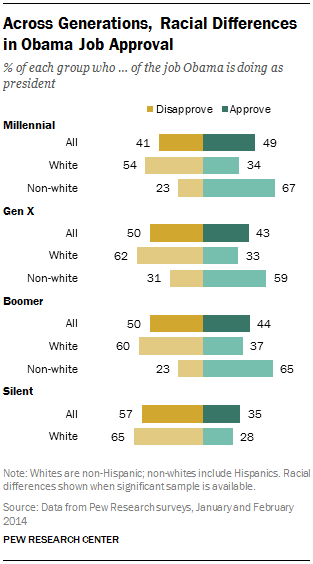

simple example, President Obama’s appeal among younger voters was a significant part of the narrative in the 2008 election.

simple example, President Obama’s appeal among younger voters was a significant part of the narrative in the 2008 election.